Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Protecting people, assets and information

Our Approach

Experience our meticulous and accountable approach towards risk management at GRC Group.

Delivering accuracy and accountability. Our approach to managing your risks is:

1. Standards-based

2. People-centred

3. Place-specific

4. Data-driven

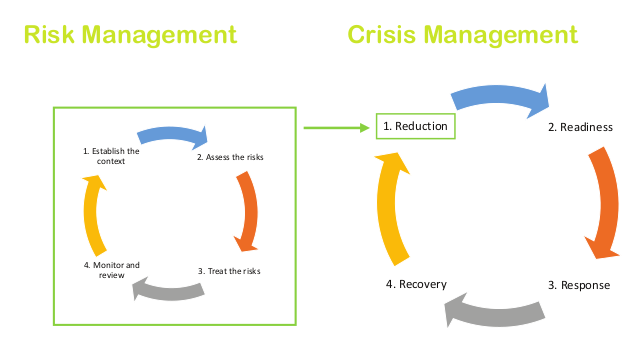

Our risk management methodology is based on the ISO 31000 Risk Management standard, which breaks the risk management process down into four distinct stages:

Our crisis management methodology is based on the NZ ntegrated approach to civil defence emergency management, which NEMA describes in terms of four areas of activity:

This standard is the international benchmark for identifying, assessing and treating risks, and it informs NZ Government guidance in areas such as Protective Security (PSR) and Work-place Health & Safety.

The starting point for the ‘four Rs’ is ‘Reduction’, which involves analysing long-term risks to life and property from hazards; taking steps to minimise their likelihood and impact. ISO 31000 provides us with the methodology for doing this.

Importantly, our methodology takes the individual or community as its starting point, establishing their relationship with and appetite for risk, and the potential impact of risks on their goals.

The ‘four Rs’ provides a framework that looks beyond a crisis to consider steps tthat should be taken well in advance and steps for future resilience.

GRC Group has developed a model for understanding, analysing, and mitigating risks to security and wellbeing. It starts with a definition and taxonomy of hazards that harnesses the dual lens of:

and order within nation-states and on predominantly military, national security, and law enforcement responses.

Understanding security from the perspective of humans and their communities necessitates a multi-layered understanding of security based on the various spaces an individual inhabits, including their homes, communities, workplaces, and societies, and the climatic and geological systems within which these spaces exist.

As defined by the United Nations Human Security Unit, ‘human security’ is a:

… comprehensive framework for

addressing widespread and cross-cutting threats. Recognizing that threats to individuals and communities vary considerably across and within countries, and at different points in time, the application of human security calls for an assessment of human insecurities that is people-centred, comprehensive, context-specific and prevention-oriented.

Why is this important? The concept of human security is critical in strengthening the resilience of individuals and their communities – particularly vulnerable communities, both during and between crises. Developing a better understanding of the myriad ways in which hazards can threaten the security of people can lead to better, more effective, more inclusive policy and decision making.

According to the UN’s Human Security Handbook (2017), a ‘people-centred’ approach focuses on attributing “equal importance to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of individuals and communities”.

Importantly, being people-centred means that human security stands as an alternative to traditional state-centric approaches to security, which are focused on threats to the sovereignty of

Organised crime, COVID-19, and climate change, for example, impact on different communities in different ways. In the case of COVID-19, associated health outcomes, employment impacts,

access to services, family harm impacts, and vulnerabilities to cyber scams have distinct patterns from one community to another.

If an individual remains distant from a hazard, it is less likely the hazard will result in harm to them. Conversely, if an individual and a hazard are located at the same place and at the same time, then the likelihood of harm (i.e. risk) to the individual is heightened.

This is a law that holds true no matter the hazard – earthquake, weather event, crime or traffic incident.

play host to disproportionately more traffic incidents than others. In the case of natural disasters, location can play a part in extreme weather events, tsunami, flooding, landslides, and geological events, and the consequences of climate change tend to differ across geographies.

We also know that this law plays out digitally as well. Expsoure to sources of misinformation and connection with perpetrators of hate online. The good news: if we know the locations of hazards (whether physically or online), then we can map them.

COVID-19 clustering, and physical distancing and isolation measures, for example, have demonstrated the importance of geographical proximity in the context of virus transmission and expsoure to potential harm. Place is thus a key element in both the spread and the containment of the pandemic.

In the case of crime, law enforcement concepts such as environmental criminology theory, routine activities theory, plac-ebased policing, and Risk Terrain Modelling (RTM) demonstrate the

importance of location to risk. Many place-based policing theories describe the role of place in shaping how crimes cluster and form ‘hotspots’, emphasising the role of place as the key element

in crime.

Pleace is also important in relation to hazard categories more commonly associated with accident, chance, or ‘act of God’. Data tells us, for instance, that certain locations – or hotspots –

Locality is critical to our understanding of individuals’ security. Understanding the prevalence of hazards in particular geographies enables us to better identify, analyse and assess risk, and to achieve better security outcomes.

GRC Group’s data platforms comprehensively map a range of threats and vulnerabilities in any given environment across Aotearoa and across cyberspace.

Risk mapping allows our partners to generate a picture of the various types of hazards to which individuals and communities may be exposed, the vulnerabilities that raise their susceptibility to harm, and the myriad factors that make the potential impact of hazards so varied.

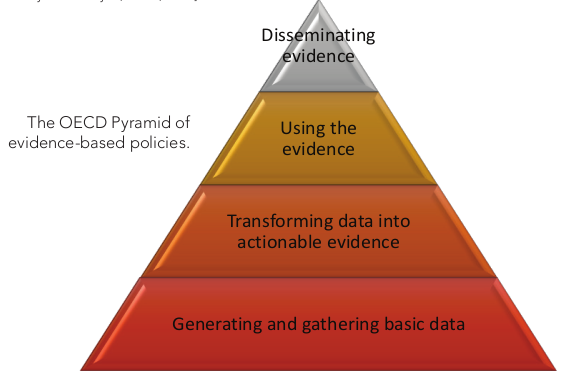

Data and open-source intelligence (OSINT) has never been more plentiful. But how do you harness the data so that it becomes the foundation for accountable evidence-based risk decision-making?

Professional security risk practice has long been hampered by the lack of an evidence basis:

Security risk assessment is often accompanied by great uncertainties, as there is a lack of evidence of threats, consequences and the abilities of security measures. Thus, qualitative or semi-quantitative models that strongly rely on expert knowledge are often used, although these models can lead to misleading or even wrong results.*

*[A Study on the Influence of Uncertainties in

Physical Security Risk Analysis, ESRA, 2018]

Our risk and crisis management solutions are purposefully data driven, transforming data into actionable intelligence for strategic foresight.

Evidence-based risk assessment (EBRA) is the practice of making risk decisions through the judicious identification, evaluation, and application of the most relevant, quantifiable, and statistically valid risk information.

The data-driven, evidence-based approach avoids decision making based on (i) intuition or instinct, and/or (ii) anecodatal or archaic example, and instead provides analysts and decision makers

with the tools they need to make the best informed decisions.